Some think of fire as a great leveller, uninterested in wealth or social status. After all, even the Queen has had a fire in her home. The truth, however, is very different: incidents of fire are not distributed evenly through society, but tend to be concentrated among poorer and more marginalised communities.

The shocking deaths of at least 80 people inside Grenfell Tower, a council housing block located in one of London’s wealthiest boroughs, brought into sharp focus what a small but growing number of studies have identified over the years: the link between rates of fire and various aspects of poverty and social deprivation.

One UK-based study of child injuries, for example, found that children whose parents were long-term unemployed were a staggering 26 times more likely to die of fire-related injuries than children whose parents were in higher managerial and professional occupations.

Another UK study, commissioned by the government, revealed clear links between rates of fire and deprivation – as well as people who were living alone, and those who had never worked. Similar patterns have been found in Australia, while in the American east-coast city of Philadelphia, the poorest grouping of residents were found to be 3.2 times more likely to have at least one child fire death in a year.

Recent efforts to bring down the rate of fire in the UK have had considerable success, with the number of incidents of fire in the home falling by 42% in the first 15 years of this century. But has this had any impact on the links between fire and deprivation?

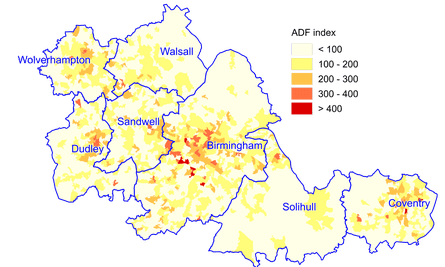

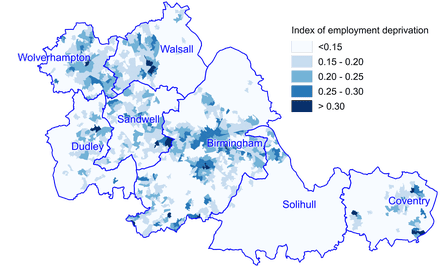

To find out, I looked at the location of accidental home fires attended by the West Midlands Fire Service, a large metropolitan fire service in the UK, in the three years up to August 2013; then compared this information with data about the socio-economic and demographic characteristics of the area.

The study turned up some striking inequalities – most notably, in factors relating to economic disadvantage such as income, health, housing overcrowding and underemployment.

One of the strongest relationships was with unemployment. Comparing rates of fire in the home between the 10% of neighbourhoods with the highest and lowest levels of employment deprivation, I found the most deprived areas to have fire rates 3.4 times higher than the least deprived.

Similarly, rates of fire in the 10% of neighbourhoods with the highest score on the Index of Multiple Deprivation were 3.7 times those in the 10% of neighbourhoods with the lowest score, and these patterns were repeated throughout many factors related to economic and social disadvantage.

Looking at the ethnic makeup of neighbourhoods, I also found a strong relationship between rates of fire and the proportion of people from black African and black Caribbean backgrounds living in an area: the ratio of fire rates between the areas with the highest and lowest numbers of black residents was 3.2:1. Importantly, this relationship held even when other factors were allowed for – that is, the relationship is not simply there because areas with large black populations also tend to have higher levels of unemployment, poverty or other factors associated with elevated rates of fire.

Finally, I also found the number of single-person households in an area to be strongly associated with rates of fire – and, oddly, that this relationship was much stronger when considering only single-person households aged under 65 (when the ratio between the highest and lowest deciles was 3.1:1).

Why such marked inequalities in the way fire is distributed continue to exist is far from clear, and remains under-researched. One factor in the link with unemployment is simply that those who are unemployed are likely to spend more time in their homes. In other cases, cultural practices may be significant – for example, a Tanzanian man I spoke to was in little doubt as to the principal factor for those in his community: a lot of deep fat frying.

Of course, smoking materials play a large part in initiating fire, and smoking is more prevalent among poorer communities (this also ties fire inequality to the wider issue of health inequality). Other possible reasons for fire inequality include poorer quality housing, overcrowding, and the inability to afford modern, safer furniture or electrical equipment.

While it is important to stress that the underlying factors of fire are not the fault of those affected, part of the difficulty in trying to tackle this inequality may lie in the fact that those most affected do not always recognise the issue.

For example, the Manor Farm estate in Coventry has a rate of accidental fires in the home over four times higher than the average in the West Midlands, and ranks sixth out of 1,680 neighbourhoods. At the time of the 2011 census, 42% of adult residents there had not worked for at least five years.

Yet when I told one resident how her neighbourhood compared to others, she sounded incredulous, saying: “Fires? … I’ve been here 30 years and I can only remember two. That’s why I’m quite surprised when you say that we’re sixth.”

While a small number of high-profile, catastrophic fires may capture the media’s attention (London experienced another major fire in Camden Lock market in the early hours of Monday morning), the vast majority are contained to the room in which they started, and only a few close neighbours will ever know about them. And so, for many people, fire seems a remote danger compared to the immediate and pressing problems of their daily lives.

Despite falling rates of fire, and the active targeting of fire safety initiatives towards at-risk groups, there continue to be marked inequalities in the way in which fire is distributed. Understanding why fire affects some communities more than others, and what can be done about it, is an important challenge for those concerned with tackling inequality – and a challenge that deserves greater attention.

- Chris Hastie (@tipichris) recently completed a PhD at the Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University. This research made use of National Statistics and Ordnance Survey data, used under the terms of the UK Open Government Licence.

- Follow the Guardian’s Inequality Project on Twitter here, or email us at inequality.project@theguardian.com

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion